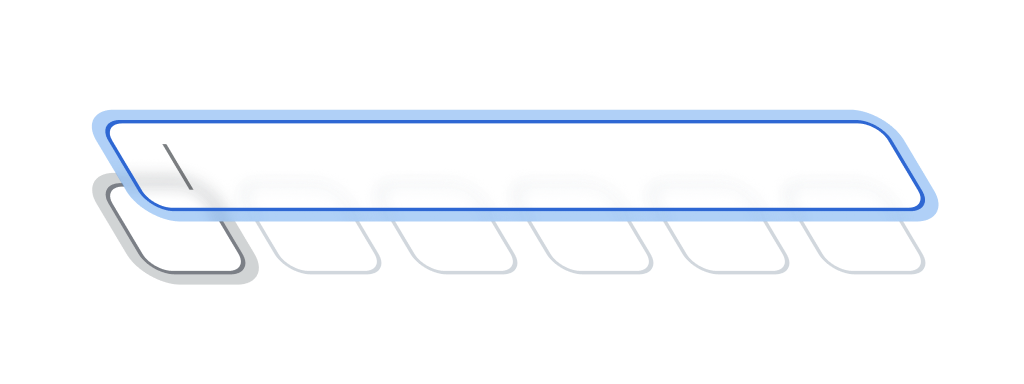

rci is a React component that ask for a one time password, in a pretty clever way. rci uses a single DOM input element, overlayed on top of plain divs for styling. Most other implementations of this pattern are based on multiple inputs. Using multiple inputs gives out-of-the-box style consistency, but comes with the disadvantage …

Continue reading “rci — A clever React Component for One-Time Passwords (OTP)”