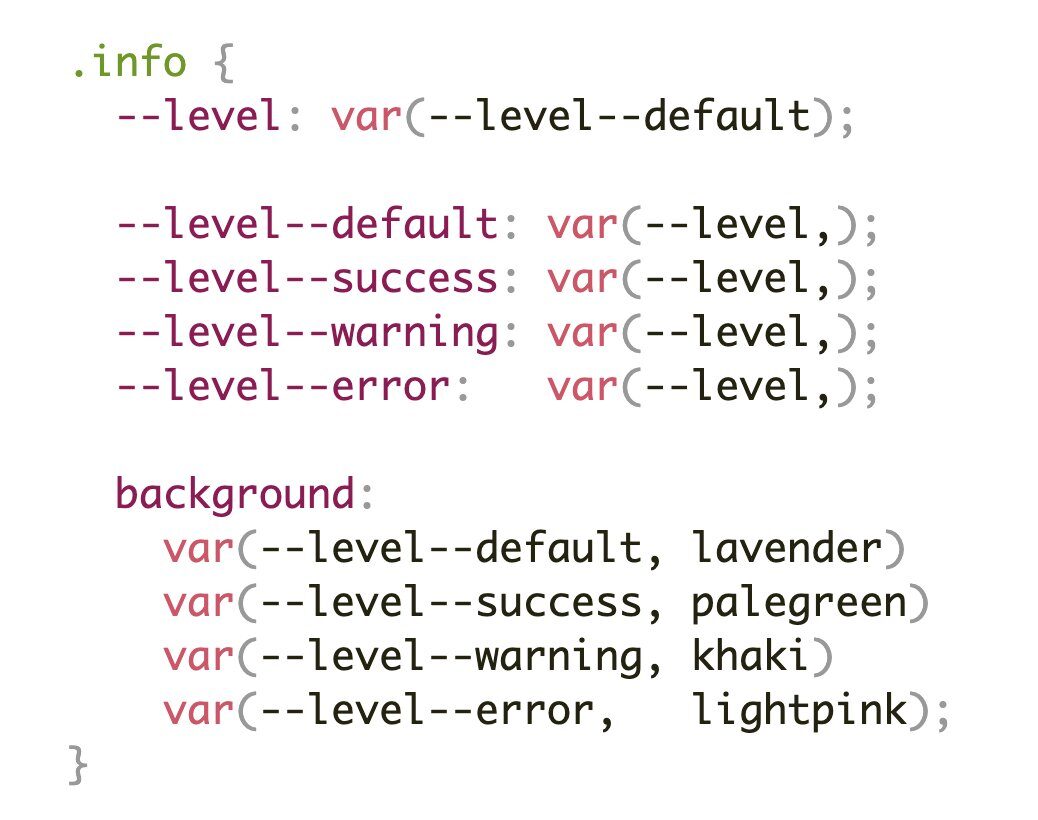

This talk by Patrick Brosset is one of my favorite talks from this year’s CSS Day Conference. How do browsers actually recalculate styles when webpages change? Can the way you write CSS impact the speed of the recalculation process? In this talk, we’ll go through the details of how browser engines react to DOM changes …