👋 This post also got published on Medium. If you like it, please give it some love a clap over there.

Earlier today, in a post entitled Secure Contexts Everywhere, it was announced on the Mozilla Security Blog that Firefox from now on will only expose new features such as new CSS properties to secure contexts:

Effective immediately, all new features that are web-exposed are to be restricted to secure contexts. Web-exposed means that the feature is observable from a web page or server, whether through JavaScript, CSS, HTTP, media formats, etc. A feature can be anything from an extension of an existing IDL-defined object, a new CSS property, a new HTTP response header, to bigger features such as WebVR. In contrast, a new CSS color keyword would likely not be restricted to secure contexts.

Whilst I somewhat applaud this move, especially in the age of data theft and digital espionage, it’s – pardon my French – quite a ballsy thing to do. CSS Properties, really?

You might not be entirely aware of it, but features like Geolocation, the Payment Request API, Web Bluetooth, Service Workers, etc. are already locked down to secure contexts only.

But what is this secure context they speak of exactly? Is it HTTPS? Or is it more than that?

Let’s take a look at the MDN Web Docs on Secure Contexts:

A context will be considered secure when it’s delivered securely (or locally), and when it cannot be used to provide access to secure APIs to a context that is not secure. In practice, this means that for a page to have a secure context, it and all the pages along its parent and opener chain must have been delivered securely.

Roughly translated: http://localhost/ is considered to be a secure context, so that one will have the latest and greatest. However, the docs aren’t that clear on whether the definition of “local” involves actual DNS resolving or not:

Locally delivered files such as

http://localhostandfile://paths are considered to have been delivered securely.

What about development domains – think project.local or project.test – pointing to 127.0.0.1? Right now we’re left in the blue here …

Do note however that Mozilla “will provide developer tools to ease the transition to secure contexts and enable testing without an HTTPS server”, but the related bug is still unassigned.

~

It’s best to have your local web development stack mimic the production environment as closely as possible. Over the years we’ve seen the rise of tools like Vagrant and Docker to easily allow us to do so: you can run the same OS and version with the exact same Apache version with the exact same PHP version with the exact same MySQL version with … oh you get the point.

One of the things that’s still not really frictionless right now for your local development domains is the use of certificates.

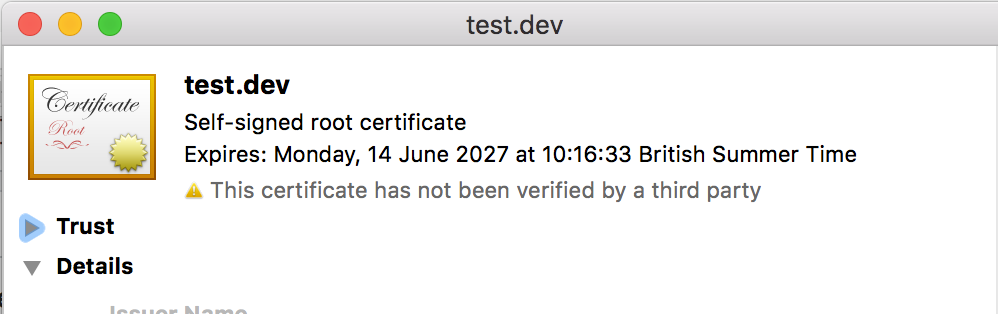

Yes, you could use self-signed certificates for this, but that’s:

- Not always possible: The Fetch API for example doesn’t allow the ignoring of self signed certificates.

- Asking for potential security problems the moment you go into production: I once read a post about some production code that still had the

--insecureflag enabled on the curl requests 🤦♂️. It was put there in the first place because of to the self-signed certificates used during development.

Another approach – and one that I am taking – is to use an actual domain for your dev needs. Each project I build is reachable via a subdomain on that dedicated domain, all pointing to 127.0.0.1 thanks to a an entry in my hosts file. Since it’s an actual domain I am using, I can use an actual and correctly signed certificate along with that when it comes to HTTPS.

At the cost of only a domain name (you can get your certificates for free via Let’s Encrypt, which now support wildcards too) that’s quite a nice solution I think.

~

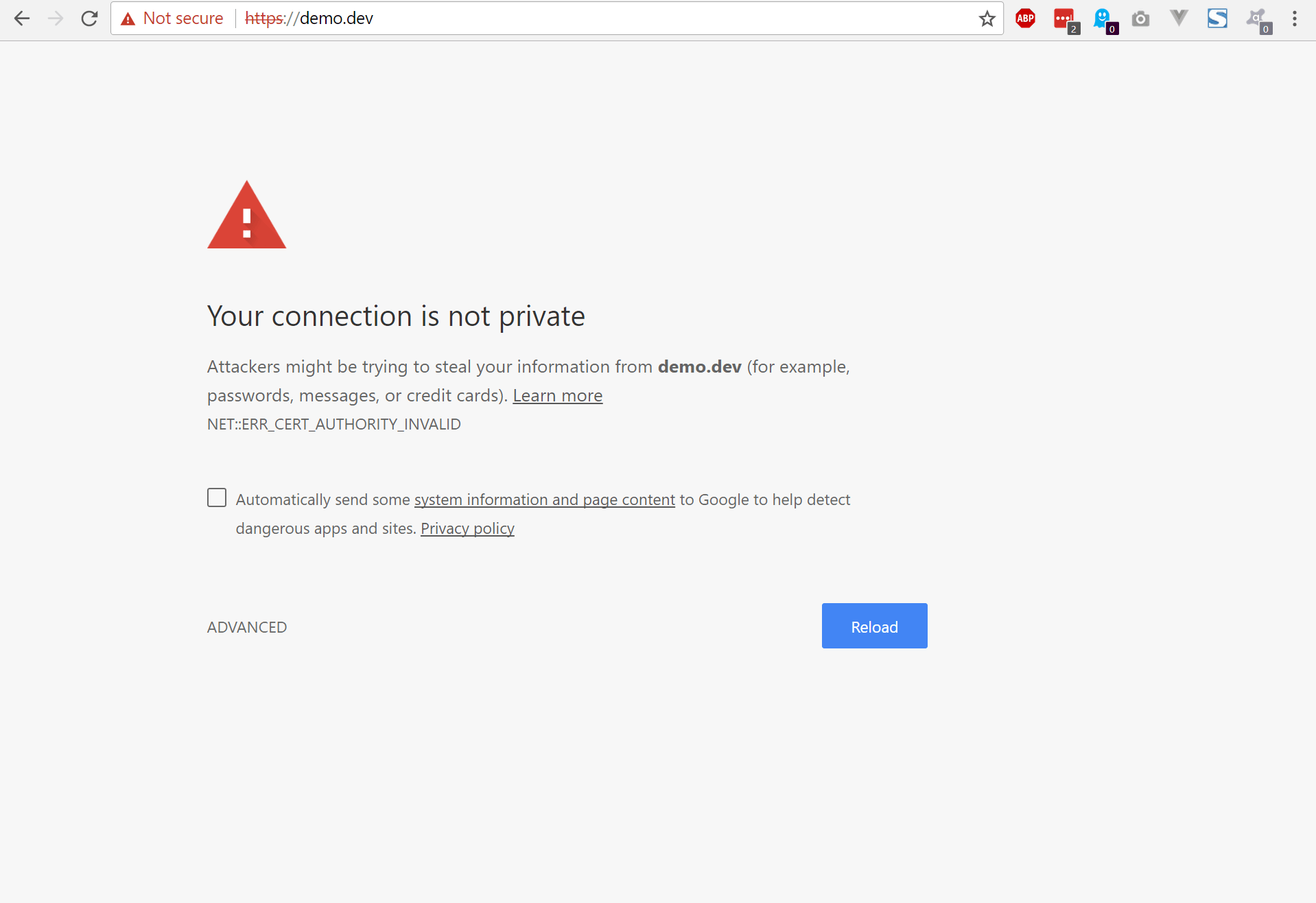

Back in December 2017 version 63 of Google Chrome was released. One of the changes included is that Chrome now requires https for .dev and .foo domains. This was ill-received by quite a lot of developers as most of them – including me before – use(d) the .dev TLD for local development purposes.

And yes, the pain is real … just do a quick search on Twitter on chrome https dev and you’ll see that lots of developer have wasted – and still are wasting – many hours on this breaking change.

Yes, there’s a (lengthy) workaround available to get the green lock in Chrome, but I wouldn’t recommend it really. It would require you to repeat a likewise procedure in all browsers you have running/are testing in, and this per .dev domain you have. Above that it won’t fix any out-of-browser contexts.

Could Google have prevented this .dev debacle? Of course. But I don’t see a reversal of this change coming any time soon though …

Can Google still do something about it? Well … I have an idea about this:

Imho Google should have opened it up, pointing all domains to 127.0.0.1 / ::1 (and more, cfr. xip.io), and providing free SSL certs for all.

That’d be … nice.

— Bramus! (@bramus) December 12, 2017

Just imagine if Google were to point all .dev domains to 127.0.0.1, that’d truly be paving the cowpaths! Add free SSL certificates for all .dev domains along with that and we’d jump quite far. With announcements like Secure Contexts Everywhere (referenced at the very top of this page) this idea seems like a real winner:

- (Chrome) Us developers can keep using the

.devTLD for projects in development. - Us developers no longer need to use self-signed certificates anymore for projects in development. We could use certificates directly signed by Google’s CA (or by Let’s Encrypt in case Google doesn’t feel like providing certificates)

- (Firefox) Domains with the

.devTLD (and with an SSL Certificate) can be considered as a Secure Context, just like any other domain reachable via HTTPS.

One can dream, right?

FIN.

Consider donating.

I don’t run ads on my blog nor do I do this for profit. A donation however would always put a smile on my face though. Thanks!

I ran into this issue on Chrome, but it turns out you can use –unsafely-treat-insecure-origin-as-secure=https://example.com to work around it!